Books: How can photographers respond to landscapes of conflict and change?

Brian Sholis

frieze, No. 174 (Oct, 2015)

Landscapes are never static. How can their dynamism, and the forces that shape them, be captured in still photographs? W hat balance of artistic licence and ‘documentary’fidelity best encapsulates the essence of a given place? How much written explanation is necessary as an accompaniment? Are these ques tions more difficult to answer when a place is facing environmen tal or political distress? Or if it is resolutely foreign to the photo grapher? And how does choosing to photograph such places affect those sites in turn? Several recent photobooks bring these elementary yet persistent questions to mind, and the choices made in each case suggest different routes through a tricky terrain.

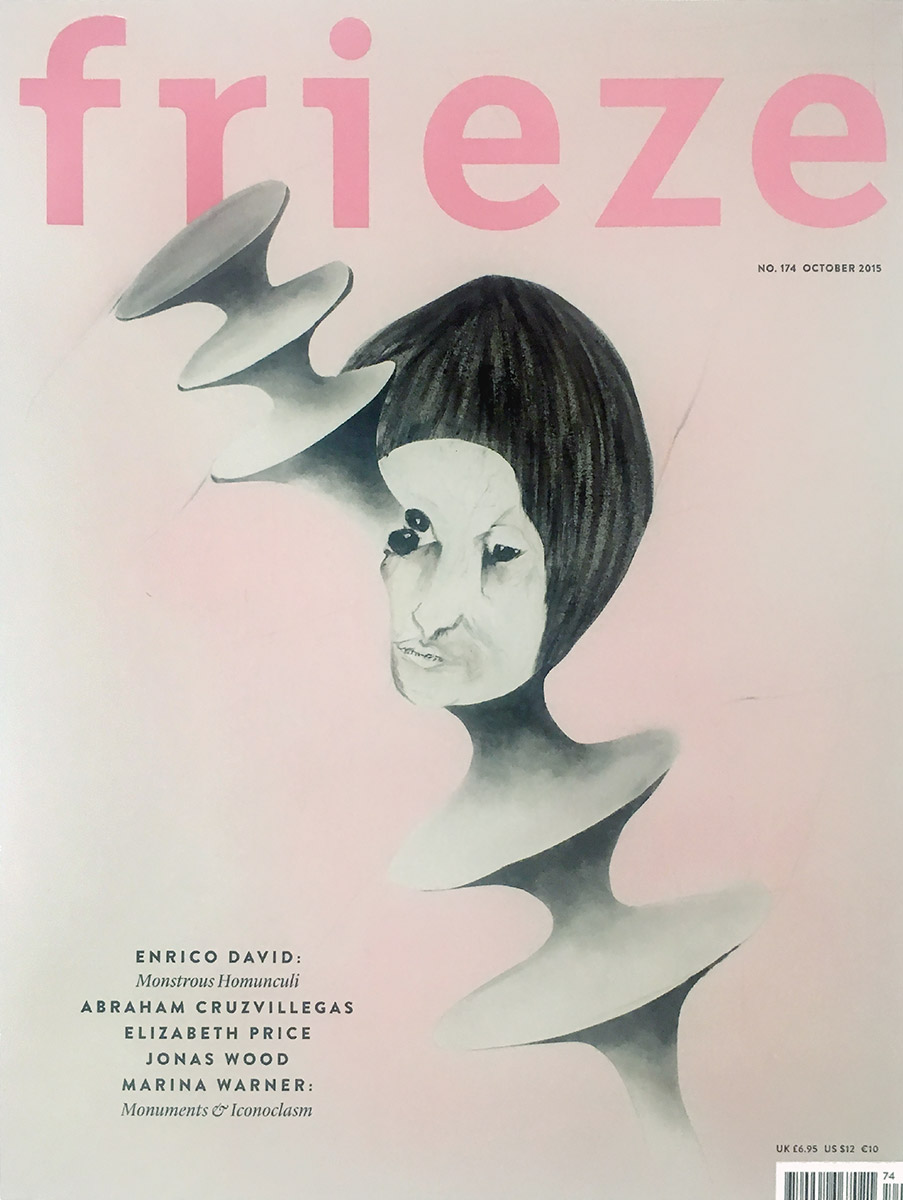

Boston- and Brooklyn-based artist Matthew Connors made the photographs in his new book, Fire in Cairo (2015), during the first six months of 2013. The adoption of the 2012 Egyptian Constitution and the summertime ousting of president Mohamed Morsi bookended this tumultuous period, and his pictures depic a city shredded by antagonism. Fire in Cairo’s opening images seem deliberately ambiguous. Is the atmosphere festive or calam itous? Without context, we’re unsure if the green lights we see are in a nightclub or are created by a gun’s laser sight, or whether the haze is from smoke machines or bombs. The first figure we encounter wears a reflective mask and a hood with colourful trim, like a disco Darth Vader. The ambiguity falls away quickly, however, and more than half of the book plunges viewers directly into the conflict. Buildings and cars are torched, graffiti covers the walls, smoke lingers in the air and helicopters loiter overhead. Tellingly, people mask their faces.

Three-quarters ofthe way through the photographs, however, Connors inserts two pictures of fire that seem to erupt from a dark void. Fire is destructive, but it can also be cleansing, and after these images come portraits of 19 seemingly ordinary citizens. Here, Connors switches to black and white, and the background recedes as his subjects remove their masks and stare placidly into the lens. The images are remi niscent ofthe hundreds he made for GeneralAssembly (2011-12), his ambitious catalogue ofOccupy Wall Street protestors. But, importantly, each spread features not one but two nearly identical portraits. They seem sequential, as if Connors had captured them with something akin to the camera’s (aptly named) ‘burst mode’. The gesture inserts his subjects back into the flow oftime, suggesting, perhaps, that their lives will not be arrested by a single moment of violence. The implied continuity augurs hope.

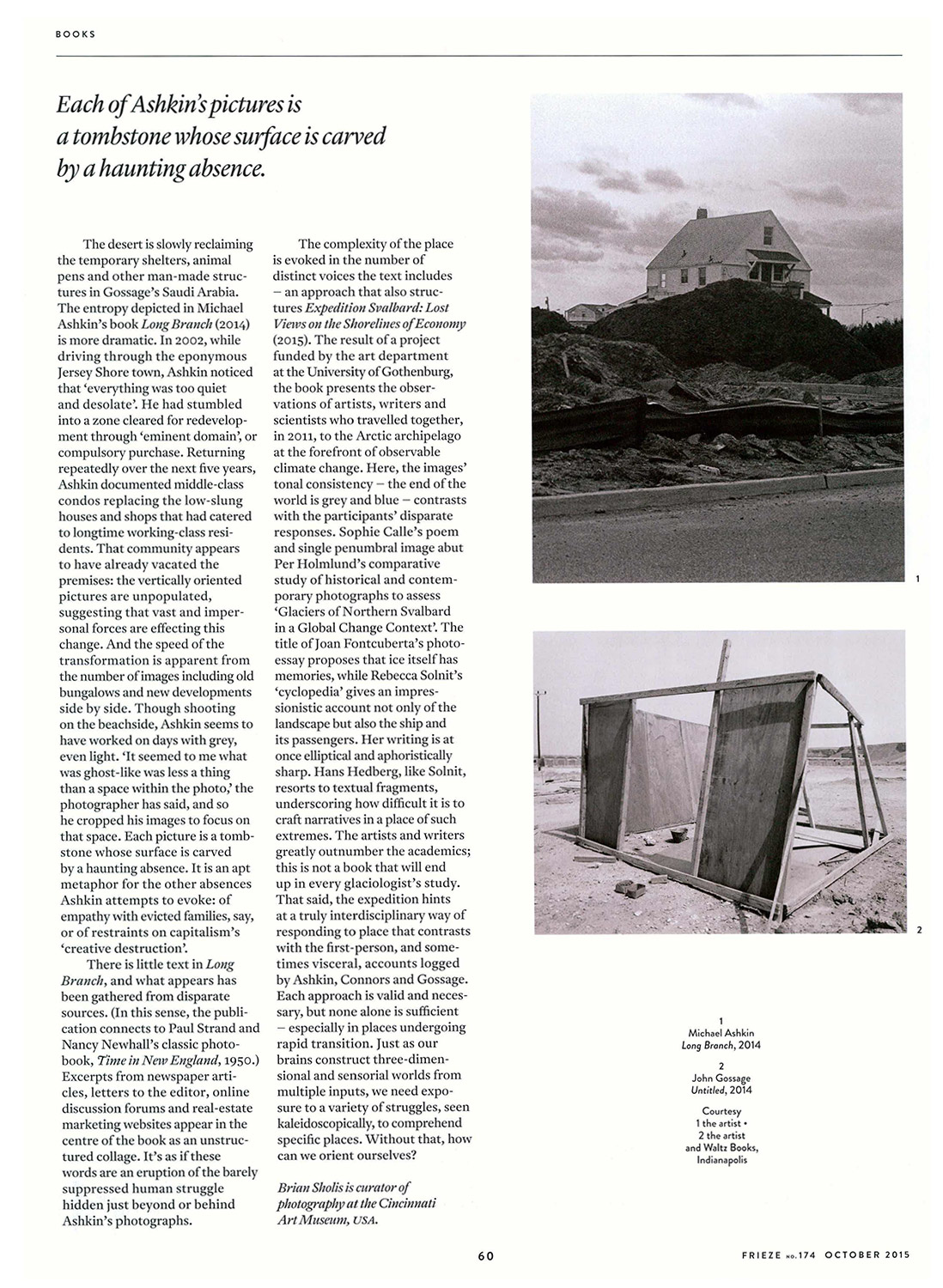

Birds in flight are another symbol of hope, and a picture of them against a blue sky connects Fire in Cairo to Nothing (2014), John Gossage’s very different book of pictures from the Middle East. Gossage’s birds circle above Saudi Arabia: he was extended an open invitation to photograph them for a month in the early 1980s. Thirty years later, his pictures take elegant form in this three-part volume. Gossage, an avid maker and collector of photobooks, has crafted a cloth- bound double-fold structure that encases two 32-page booklets and a two-metre-long foldout.

Whereas Connors’s book contains a short story written by the artist, Gossage’s includes only four sentences of text. The artist announces he wants to venture into the desert and is told by Prince Abdullah: ‘You know, there is nothing out there.’ The book’s 24-image foldout, a pano ramic view of a barren desert landscape, suggests the gran deur of that ‘nothing’. But, of course, there is much to behold, and Gossage finds much to savour. A rubbish-strewn pile

of dirt, sprinkled with rotting fruits, has a pattern-like all-over composition. Arabic graffiti in black spray paint on a rocky hill side is a masterclass in depicting texture. Paths or doorways lead one’s eyes deep into some pictures, while great stone edifices block the view into others. The sequencing, especially in the first booklet, emphasizes composi tional variety and visual pleasure more than any particular narra tive, though it’s apparent that Gossage is circumnavigating the edges of a town or city. The second booklet is more explicitly ‘political’in its subject matter. Here we see the artist’s visa, a torn cardboard box stamped ‘MADE IN U.S.A.’, barbed wire, oil barrels and, in addition to those birds in flight, a Saudi man in a tradi tional thobe grasping the wings of a white, dove-like bird. Given the acknowledged brevity of Gossage’s visit, and the distance between what he knows and what he’s photographing, I prefer the more equivocal of the two selections. In its near-total anonymity, the first booklet creates space for viewers to look carefully and make deductions; its openness to inter pretation is more closely aligned with Gossage’sbestwork. But both booklets showcase his ability to transform quotidian scenes into exciting photographs.

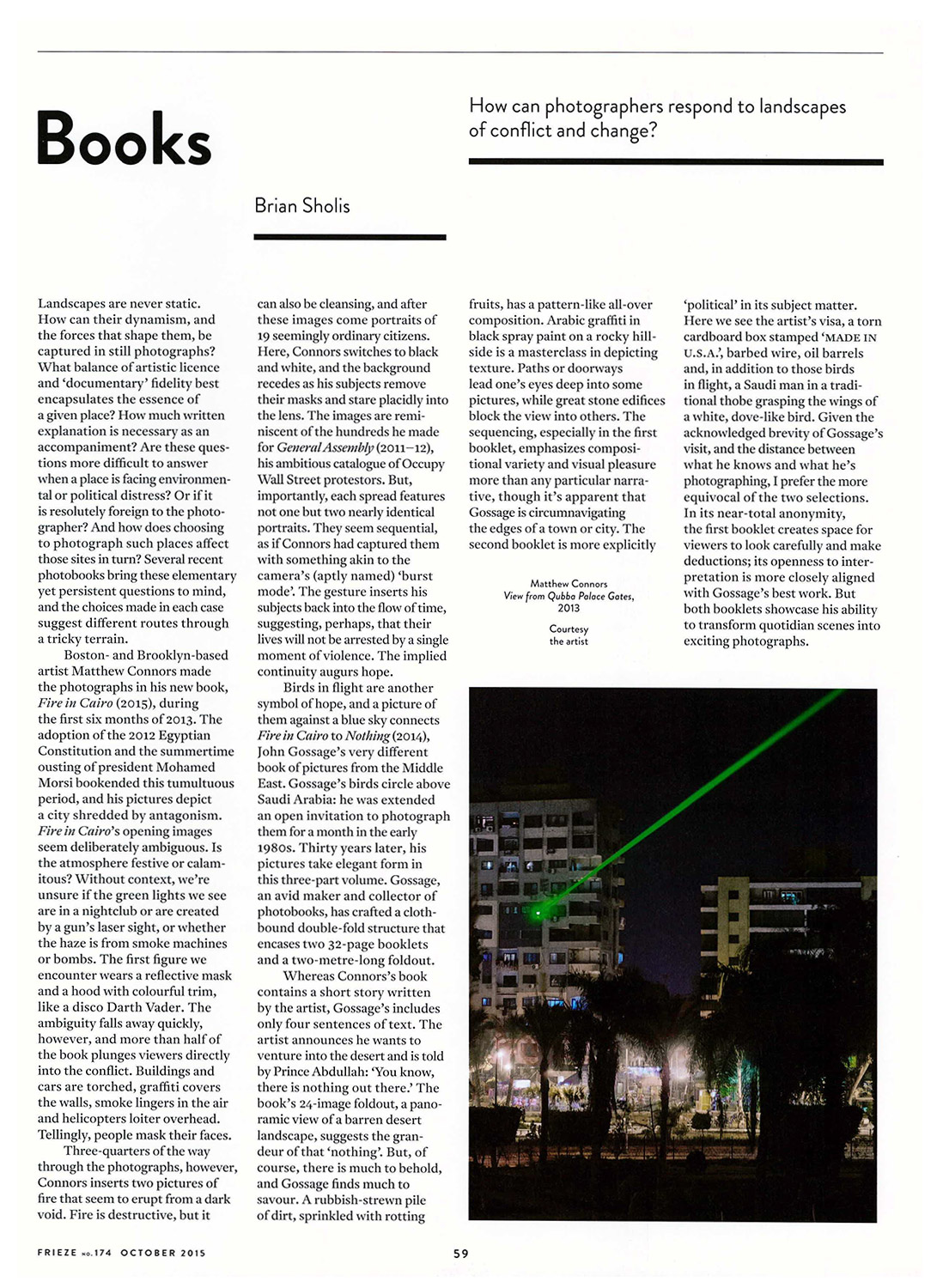

The desert is slowlyreclaiming the temporary shelters, animal pens and other man-made struc tures in Gossage’s Saudi Arabia. The entropy depicted in Michael Ashkin’s book Long Branch (2014) is more dramatic. In 2002, while driving through the eponymous Jersey Shore town, Ashkin noticed that ‘everything was too quiet

and desolate’. He had stumbled into a zone cleared for redevelop ment through ‘eminent domain’, or compulsory purchase. Returning repeatedly over the next five years, Ashkin documented middle-class condos replacing the low-slung houses and shops that had catered to longtime working-class resi dents. That community appears

to have already vacated the premises: the vertically oriented pictures are unpopulated, suggesting that vast and imper sonal forces are effecting this change. And the speed ofthe transformation is apparent from the number ofimages including old bungalows and new developments side by side. Though shootin on the beachside, Ashkin seems to have worked on days with grey, even light. ‘It seemed to me what was ghost-like was less a thing than a space within the photo,’the photographer has said, and she cropped his images to focus on that space. Each picture is a tomb stone whose surface is carved by a haunting absence. It is an apt metaphor for the other absences Ashkin attempts to evoke: of empathy with evicted families, say, or of restraints on capitalism’s ‘creative destruction’.

There is little text in Long Branch, and what appears has been gathered from disparate sources. (In this sense, the publi cation connects to Paul Strand and Nancy Newhall’s classic photo book, Time in New England, 1950.) Excerpts from newspaper arti cles, letters to the editor, online discussion forums and real-estate marketing websites appear in the centre of the book as an unstruc tured collage. It’s as if thes words are an eruption ofthe barely suppressed human struggle hidden just beyond or behind Ashkin’sphotographs.

The complexity of the place is evoked in the number of distinct voices the text includes —an approach that also struc tures Expedition Svalbard: Lost Views on the Shorelines o fEconomy (2015). The result of a project funded by the art department at the University of Gothenburg, the book presents the obser vations of artists, writers and scientists who travelled together, in 2011, to the Arctic archipelago at the forefront of observable climate change. Here, the images’ tonal consistency - the end ofthe world is grey and blue —contrasts with the participants’disparate responses. Sophie Calle’s poem and single penumbral image abut Per Holmlund’s comparative study of historical and contem porary photographs to assess ‘Glaciers of Northern Svalbard in a Global Change Context’. The title ofJoan Fontcuberta’s photo essay proposes that ice itself has memories, while Rebecca Solnit’s ‘cyclopedia’gives an impres sionistic account not only ofthe landscape but also the ship and its passengers. Her writing is at once elliptical and aphoristically sharp. Hans Hedberg, like Solnit, resorts to textual fragments, underscoring how difficult it is to craft narratives in a place of such extremes. The artists and writers greatly outnumber the academics; this is not a book that will end up in every glaciologist’s study. That said, the expedition hints at a truly interdisciplinary way of responding to place that contrasts with the first-person, and some times visceral, accounts logged by Ashkin, Connors and Gossage. Each approach is valid and neces sary, but none alone is sufficien - especially in places undergoing rapid transition. Just as our brains construct three-dimen sional and sensorial worlds from multiple inputs, we need expo sure to a variety of struggles, seen kaleidoscopically, to comprehend specific places. W ithout that, how can we orient ourselves?