What Does a Metaphor Rest Upon?

Andrianna Campbell

Contact Sheet: Light Work Annual (Summer, 2018)

December 6, 2014 Matthew Connors and I are listening to W. J. T. Mitchell and Michael Taussig talk about monuments and their mutiple-authored book Occupy: Three Essays in Disobedience. Connors is furiously taking notes, scribbling. It makes sense; he has been laying out his own book, Fire in Cairo, on the uprising in Egypt. Also we are in the midst of planning a trip to Cuba to document the end of the Castro era, and changes in the country’s relationship to monumentality. How could we know then, the two of us, collaborators and friends, so invested in the intersection of art and politics, how could we predict the immeasurability of changes here in the era of Donald J. Trump?

Connors’s photographs of the protests since the election of Trump are consistent with his conceptual and imagistic preoccupations throughout his oeuvre. There is so much here that reminds of the documentary, of Magnum’s Frank Capa, of his brother Cornell Capa whose “concerned photography” was a means of using the image for humanitarian aims in the wake of post-World War despair. Yet, Connors is not of their ilk and we should find it no coincidence that he is a fan of the fiction of Donald Barthelme. Because wasn’t it Barthelme writing about the aim of literature who said it “is the creation of a strange object covered with fur which breaks your heart.” These photographs are like this. They are so disconcerting and so tender.

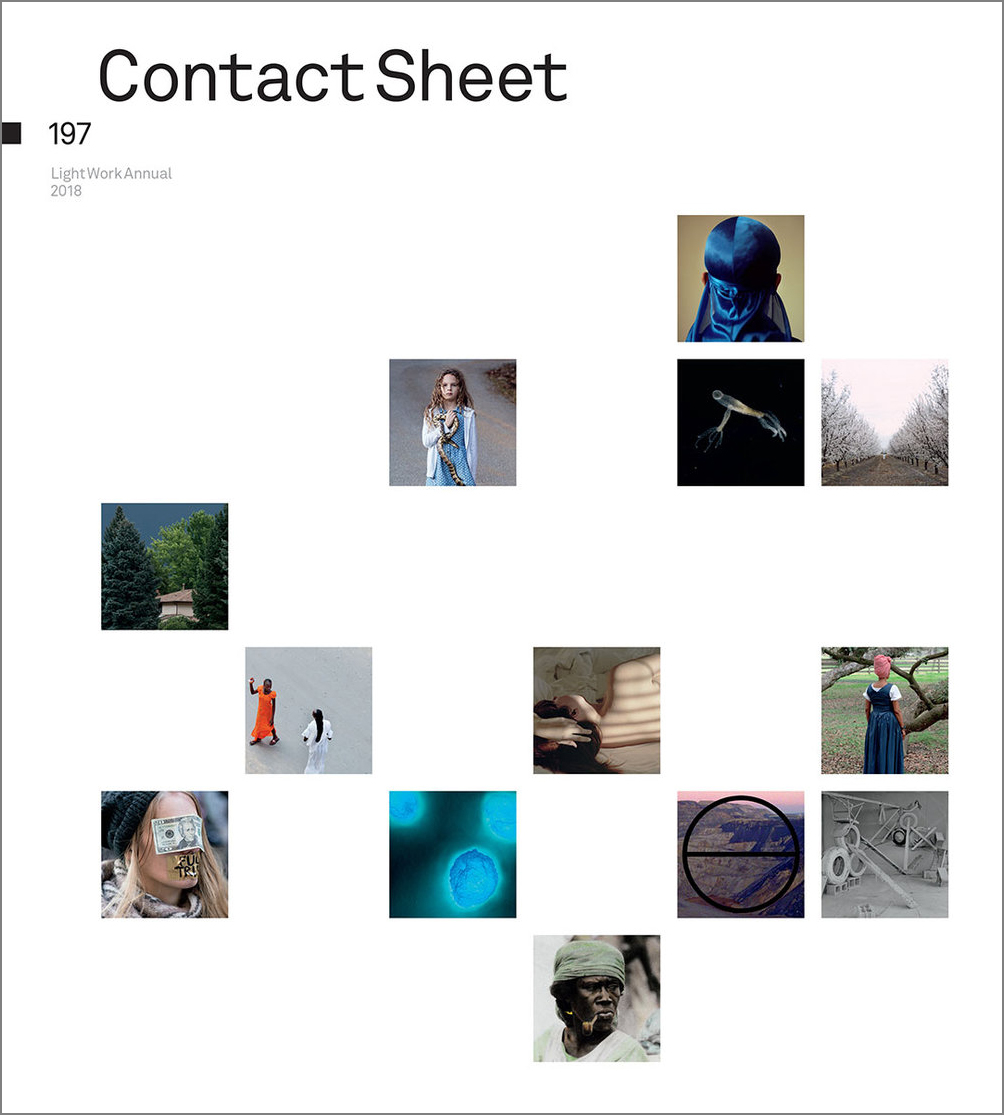

Rather than approaching his subjects as that which may be narrated, Connors settles on the often inexplicable in the crowd. In FUTR 2016, a blonde woman is depicted with a $20 bill glued over her eyes, her lips gagged by gold duct tape. How does she see to march? She has sharpied “Fuck Trump” on the tape. We don’t need to hear her rally cry, because her lament was made to be pictured. The strangeness of the image though indicates directness is not what is being sought. This brings us to a second poignant point about these photographs; Connors likes to introduce the accouterment of resistance. In Mask in Reverse 2016, we see the back of a mask that is a ruler, tape, and wire. The blank white verso of the cut out faces us. The photograph gives us little information about the author or person pictured. Whose face is on the front? It is most likely Trump’s face, but it could be anyone. We have and have had so many crooks in office. The anonymity of the missing face, the blank spots, we fill in from memory. I used to picture Nixon. This was how we were trained from cinema. Think Point Break 1991. I now know that it was all the previous presidents but in my memory it was only Nixon.

Nixon was our presidential bad guy. Will Trump’s face ever achieve this ubiquity in parody? By denying us his visage, Connors continues his concentration on the inexplicable. So we enter his photographs, framed by a want of the traditional interaction with the documentary and then are derailed. Take for instance Flame 2017, where the window of a limousine becomes the classic Albertian example of the pictorial window onto another world. The fire in the backseat is an abstraction, and as you look in through a pile of jagged broken glass, you begin to understand its cause. Then in Tower Interior 2016, there is the reflection of lights as you traverse the landscape horizontally. This dystopian vantage point reveals itself in Trump Tower after just one escalator ride. Overall there is a vulnerability to these images, which captures the nature of mounting a resistance to adamantine corporate and state goliaths.

There are moments that we are reminded that Connors is there. These are very much informed by his presence in the space alongside the protestors. In Pussy Balaclava 2017 a woman in a cat mask quizzically eyes him. Her eyes seem weary but determined. It is these cold days that deter bodies in the streets, but she is here and has donned a cat mask. How does it relate at all to why she is here? What does the cat metaphor rest upon? This is what we want to know. In this case, there is no metaphor. In this case, the monument is invisible. There are no statues to tear down as we have in our past with Robert E. Lee and other members of the Confederacy. Our targets have become inaccessible to the crowds; their power concretized in monuments of steel and glass impenetrable by the human scale. It is the invisibility of the monuments, the obscurity of the faces, and the often illegibility of the textual that informs Connors’s praxis. And it is the cars on fire, the fragility of the homemade mask, the shaking handwritten script of the sharpie that reminds of the invisible and metaphoric slingshots dispersed in the crowds.