The Berber Uprising

Matthew Connors

We defended the city as best we could. The enemy’s rocks came in waves and their clubs clattered on metal barriers in deafening, syncopated roars. There were torched palm trees along Midan Simon Bolivar where the epauletted revolutionary watched dispassionately from his stone perch. Large sheets of marble facade had been torn from the Intercontinental Hotel and smashed for weaponry. Our senses were consumed in confusion. On the small balcony that shielded our intimacies, I asked her if she could be happy here. It had been a cold spring, but the mosquitos still came for us at night. She didn’t answer. We sat amongst neglected items: salvaged records, moldered sushi, cracked chairs, a book of ingenious mechanical devices, court documents, two stray cats, the everydayness of resistance.

Armed patrols in riot gear guarded the interior. We built concrete cube walls around the tallest buildings so we would not be surprised from any direction. The rebels routinely set our barricades on fire, but we responded from above with imported tear gas and some rocks of our own. They were making paintings in the square to discredit us again.

“Why are we fighting them?” I asked.

“They’re mad. We’re sane,” Sherif replied.

“But don’t they also consider themselves sane?”

“I think they know. Deep down. They fight more fiercely in order to deny what they know not to be true. They are not sane.”

Masked men in tight, cheap clothes marched on our position with ugly cudgels and gasoline bombs. They had been holding vigil all night in the old stadium singing chants and shaking their hands to get in the mood. Some fired wildly at us with homemade bearing guns and attempted to blind us with lasers. The Brigadier General ordered us to hold the sector while Sherif fired sniper rounds from the upper floor of a building designed by Edward Matasek. He targeted known transcendentalists, firing efficient shots deep into their chest cavities. I decided I knew nothing. The rebels pulled back to the river in a feigned retreat and hastily reinforced their battalion with cabdrivers and potato vendors. They returned with lacerated photographs of the President’s face. This force was crushed by late afternoon on a day that had begun with a quiet meal of soft cheese wrapped in white bread.

This is the spot on the balcony where Shady used to give us haircuts at night. He worked deliberately under incandescent lamps, moving his hands in unpredictable rhythms. Afterward, he hosed the clippings off our bodies until they swirled in cold puddles with invincible glitter from another time. Those days we could still hoard duty free. Strangers stumbled out of threesomes into awkward conversations and danced recklessly with frustrated non-governmentals. I sat there getting drunker and drunker, measuring my love. She watched me closely, keeping meticulous notes on all the defects between us. Contingency angered her. I responded with some random vile things, not only because she expected me to but also because I enjoyed it.

Phalanxes of bareheaded women entered the scene and the situation became liquid. People were running through the square, scattered by something tragic and sudden. Fires flashed from makeshift blowtorches and the crowd dissolved into a viscous mass of red and black. Flare smoke enveloped the street in an orange fog cutting off our visibility. We were low on gas and tonic water, and our credit rating had been downgraded again. There was nothing to do but hold our positions and monitor the ground as best we could. I had just learned from messages flown in by Eurasian coots that today had been declared the Friday of Human Dignity. I decided I knew nothing. State television footage later revealed herds of fat men clambering toward soundless ululations to save and destroy the center that bound them into a rushing, seamless whole.

And do you remember the time we spent in the Valley of the Whales? After several weeks of heavy dreams we drove straight into the desert. The wind coursed beautifully through your hair and was so strong I had to kneel underneath the prayer mat to light the fire for tea. We sat for hours on the cliff watching dark cloud shadows drift across the soft desert basin until the evening coldness seeped into your bones. Even then I could not guarantee your safety after dark.

We interrogated the captured rebel from Tanta in the security camp on the outskirts of the city. He had a friendly disposition so I related a little of the history of torture, reviewing the recent scholarship and directing his attention to patches of dried brown liquid on the floor where flies continued to gather. I leafed past diagrams of hanging techniques and virginity tests administered by truncheons to the more modern methods – American, Russian, Chinese – that could be applied in advanced situations. Sherif made a show of transcribing the rebel’s hurried and exaggerated reports before we destroyed the documents and turned our attention to the children. Three days later the hospital accepted his naked body and relayed the tragic news of a car accident to his family.

Of all the calls to prayer, the neighbor’s dogs made the most impassioned contributions to the Dhuhr before lunch. We sat in silence through the crackling sermons eating bowls of dry cereal and basil sandwiches. If the mood struck, I would give brief lectures on the Casimir effect, the impurity of signals, or the multivariable calculus of tits and tats. But she had little patience for phenomena that worked in practice, but not in theory. Her attention drifted to her ancient instrument exacting discrete violence on its bronze keys.

“Is that Sulendro?”

“No, Sudamala,” she said. “I play it at certain times, when I am sad, or happy, although it requires four hands.”

“How is that managed?”

“I expand the tones.”

At night I walked among them in fragile anonymity searching for the Father of the Rebels. On uprooted sidewalks, I melted into downtown crowds under the suspicious gazes of provocatively posed mannequins in crotchless panties. My thoughts returned to her inanimate back. Merchants had transformed the streets radiating from the square into markets for cheap wares made in collapsing factories. Not even the cabdrivers could argue their way through. Agents with gelled hair and short knives circulated through the district on Chinese motorcycles confiscating communication equipment from foreign collaborators and taunting the men who returned from Jihad deranged.

Sources from inside the resistance had directed my attention across the river. The island was a vestige of colonial times offering some refuge from the city’s wafting miasma of open sewers and crippled kittens feeding on discarded organ meat. Tourists came here to play out their oriental fantasies and drink black market liquids with aging bon vivants who sought shelter from puritanical sandstorms. Discrete bars along the riverfront offered small windows onto a sensual past where one could find momentary reasons to be cheerful. I sat there getting drunker and drunker surrounded by men who made small fortunes repairing the hymens of veiled women and smuggling fast food through border tunnels. We felt no urgency to rebel against the confines of our lives.

Untranslated news stories cycled through a pixelated grid on a corner television. The Court of Cassation annulled the constitutional referendum, a weapons cache was uncovered in an antique clock store on Al Sad Al Aali, another employee of the Electricity Ministry self immolated, a state of emergency had been declared in the delta region, the barricades were holding.

Then it was learned the President had made another urgent speech, speaking of situations and insisting on meaning. He had lost control of the Islamists. Men in starched white tunics peered through the bar window rousing the sleepy matron into a half-hearted tirade against the suppression of the immorals. She threatened to display the pubic hair she had shaven into the shape of a cleric’s beard, but soon settled back into her ancestral post, silently smoking next to the register.

And we can never wrap our hands together in the same way again however much we may wish to hold or clasp or cradle the brilliant body and its fermenting distempers.

He came for me after curfew on Rejection Friday wearing a surgical mask. When I resisted, he tore off my shirt. After I resisted some more, he tore off my pants and underpants. He kept telling me to stand up and I responded with my injuries. We grappled and flipped over the bannister, crashing downstairs into another situation.

The rebels smashed our defenses on three sides prompting the armed forces spokesperson to issue a destruction alert. Sirens sounded in all the metro stations and noise accumulated in the square. We killed a great many of them from helicopters, reducing their terror camps to fields of fire, but many more came from all dispositions to taste history. The President’s last known orders were to flood the tunnels and burn the petitions. A provisional government was established and detained us in aging municipal buildings while they adjudicated the bureaucracy of retribution. They spoke to me softly in a yellow room. I removed my belt and shoelaces searching the wild eyes of children for the prospect of silence.

This original story is included in Fire in Cairo

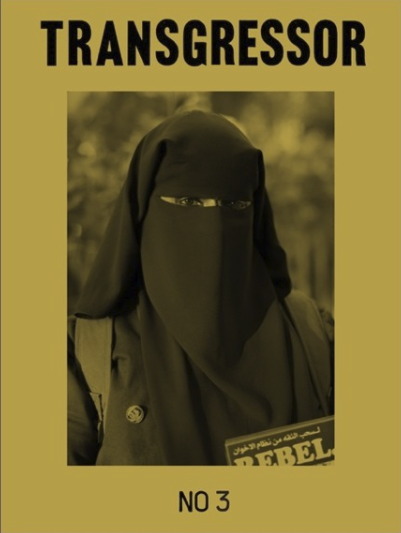

An early version of this story first appeared in Transgressor Magazine