Fire in Cairo

Lucy Davies

British Journal of Photography (June, 2015)

When in July 2013 Matthew Connors turned the key in the lock of his Brooklyn studio for the first time in a year, he had more than 27,000 image on the hard drive in his bag. A professor at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston since 2004 (he commutes once a week from New York City via train), he had spent the previous 12 months on sabbatical, travelling through Egypt and North Korea, photographing both.

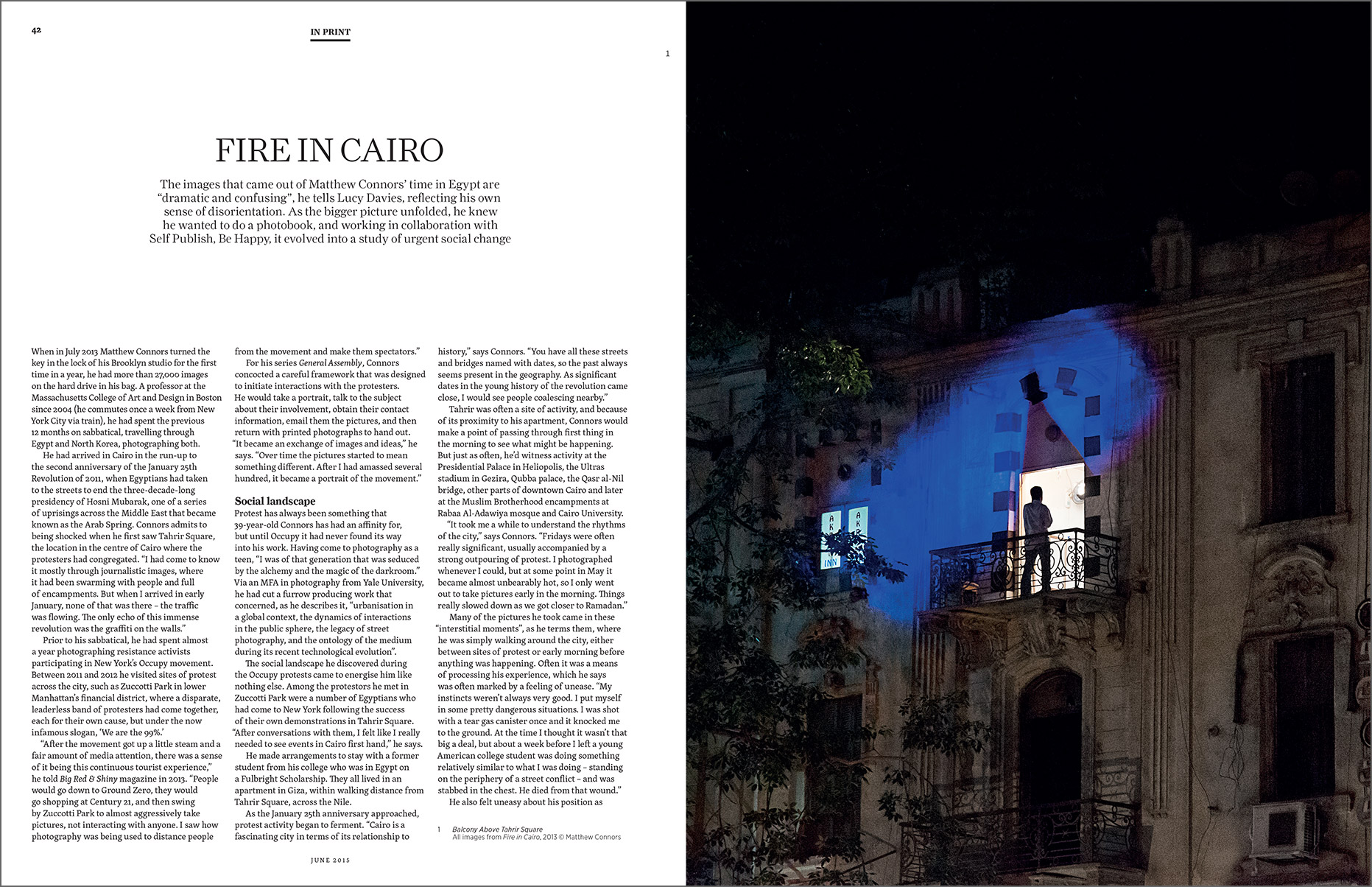

He had arrived in Cairo in the run-up tthe second anniversary of the January 25th Revolution of 2011, when Egyptians had taketo the streets to end the three-decade-long presidency of Hosni Mubarak, one of a seriesof uprisings across the Middle East that became known as the Arab Spring. Connors admits to being shocked when he first saw Tahrir Square, the location in the centre of Cairo where the protesters had congregated. “I had come to know it mostly through journalistic images, wher it had been swarming with people and ful of encampments. But when I arrived in early January, none of that was there – the traffic was flowing. The only echo of this immense revolution was the graffiti on the walls.”

Prior to his sabbatical, he had spent almost a year photographing resistance activists participating in New York’s Occupy movement. Between 2011 and 2012 he visited sites of protest across the city, such as Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan’s financial district, where a disparate, leaderless band of protesters had come together, each for their own cause, but under the now infamous slogan, ‘We are the 99%.’

“After the movement got up a little steam and a fair amount of media attention, there was a sense of it being this continuous tourist experience,” he told Big Red & Shiny magazine in 2013. “People would go down to Ground Zero, they would go shopping at Century 21, and then swing by Zuccotti Park to almost aggressively take pictures, not interacting with anyone. I saw how photography was being used to distance people from the movement and make them spectators.”

For his series General Assembly, Connors concocted a careful framework that was designed to initiate interactions with the protesters. He would take a portrait, talk to the subject about their involvement, obtain their contact information, email them the pictures, and then return with printed photographs to hand out. “It became an exchange of images and ideas,” he says. “Over time the pictures started to mean something different. After I had amassed several hundred, it became a portrait of the movement.”

Social landscape

Protest has always been something that 39-year-old Connors has had an affinity for, but until Occupy it had never found its way into his work. Having come to photography as a teen, “I was of that generation that was seduced by the alchemy and the magic of the darkroom.” Via an MFA in photography from Yale University, he had cut a furrow producing work that concerned, as he describes it, “urbanisation in a global context, the dynamics of interactions in the public sphere, the legacy of street photography, and the ontology of the medium during its recent technological evolution”.

The social landscape he discovered during the Occupy protests came to energise him like nothing else. Among the protestors he met in Zuccotti Park were a number of Egyptians who had come to New York following the success of their own demonstrations in Tahrir Square. “After conversations with them, I felt like I really needed to see events in Cairo first hand,” he says.

He made arrangements to stay with a former student from his college who was in Egypt on

a Fulbright Scholarship. They all lived in an apartment in Giza, within walking distance from Tahrir Square, across the Nile.

As the January 25th anniversary approached, protest activity began to ferment. “Cairo is a fascinating city in terms of its relationship to history,” says Connors. “You have all these streets and bridges named with dates, so the past always seems present in the geography. As significant dates in the young history of the revolution came close, I would see people coalescing nearby.”

Tahrir was often a site of activity, and because of its proximity to his apartment, Connors would make a point of passing through first thing in the morning to see what might be happening. But just as often, he’d witness activity at the Presidential Palace in Heliopolis, the Ultras stadium in Gezira, Qubba palace, the Qasr al-Nil bridge, other parts of downtown Cairo and later at the Muslim Brotherhood encampments at Rabaa Al-Adawiya mosque and Cairo University.

“It took me a while to understand the rhythms of the city,” says Connors. “Fridays were often really significant, usually accompanied by a strong outpouring of protest. I photographed whenever I could, but at some point in May it became almost unbearably hot, so I only went out to take pictures early in the morning. Things really slowed down as we got closer to Ramadan.”

Many of the pictures he took came in these “interstitial moments”, as he terms them, where he was simply walking around the city, either between sites of protest or early morning before anything was happening. Often it was a means of processing his experience, which he says was often marked by a feeling of unease. “My instincts weren’t always very good. I put myself in some pretty dangerous situations. I was shot with a tear gas canister once and it knocked me to the ground. At the time I thought it wasn’t that big a deal, but about a week before I left a young American college student was doing something relatively similar to what I was doing – standing on the periphery of a street conflict – and was stabbed in the chest. He died from that wound.”

He also felt uneasy about his position as omniscient narrator. “I couldn’t tell the story in the same way as I might have done in America,” he explains. “I was hampered by not being fluent in Arabic but, more importantly, by a general lack of expertise in the political dynamics of Egypt, which are incredibly layered. I think a lot of the work I made was conscious of that lack of authority. The pictures that came out of it are often dramatic and confusing, and that really mimics my experience there. they are highly subjective – and they are meant to be.”

Sequence and repeat

The work he made in Egypt, titled Fire in Cairo, is soon to be published under the Self Publish, Be Happy helm. “I always knew I wanted to do a book,” says Connors, “and it definitely changed the way I was thinking about photographing when I was there. The work I was making before was very much meant to be on the wall, but here I knew I wanted to incorporate writing, and when I was photographing I was o!en thinking about how the images would look in sequence and in relationship with each other.”

He also knew who he wanted to self-publish with: “More than anything I wanted to work with Bruno [Ceschel] and Tony [art director Antonio de Luca]. They had already included me in a small pamphlet they had published that had been curated by Nicholas Muellner, and I knew from that and other things they have produced that they have a real dedication to the book as an object. I think they are really pushing the boundaries of what a photobook can be, and they have the wherewithal and the imagination to do it. I wanted to be paired with that.”

The book has taken quite some time to put together, not least because he suffered what he describes as “pre"y severe whiplash going from Cairo to the States”. He started teaching again right away and transitioned into being chair of his department, “which demanded an incredible amount of my attention”. But even aside from that, he needed time to digest the original cache of 20,000 images, which he and Ceschel had to whi"le down to around 90.

His first draft was made at a friend’s cabin in Massachusetts, with nothing but his dog for company. After that, it went to Ceschel and back, to Connors’ friends and back, to de Luca and back to Connors again. The object has been a real collaboration. The way my book has developed under their guiding hands is better than I could have done on my own,” says Connors.

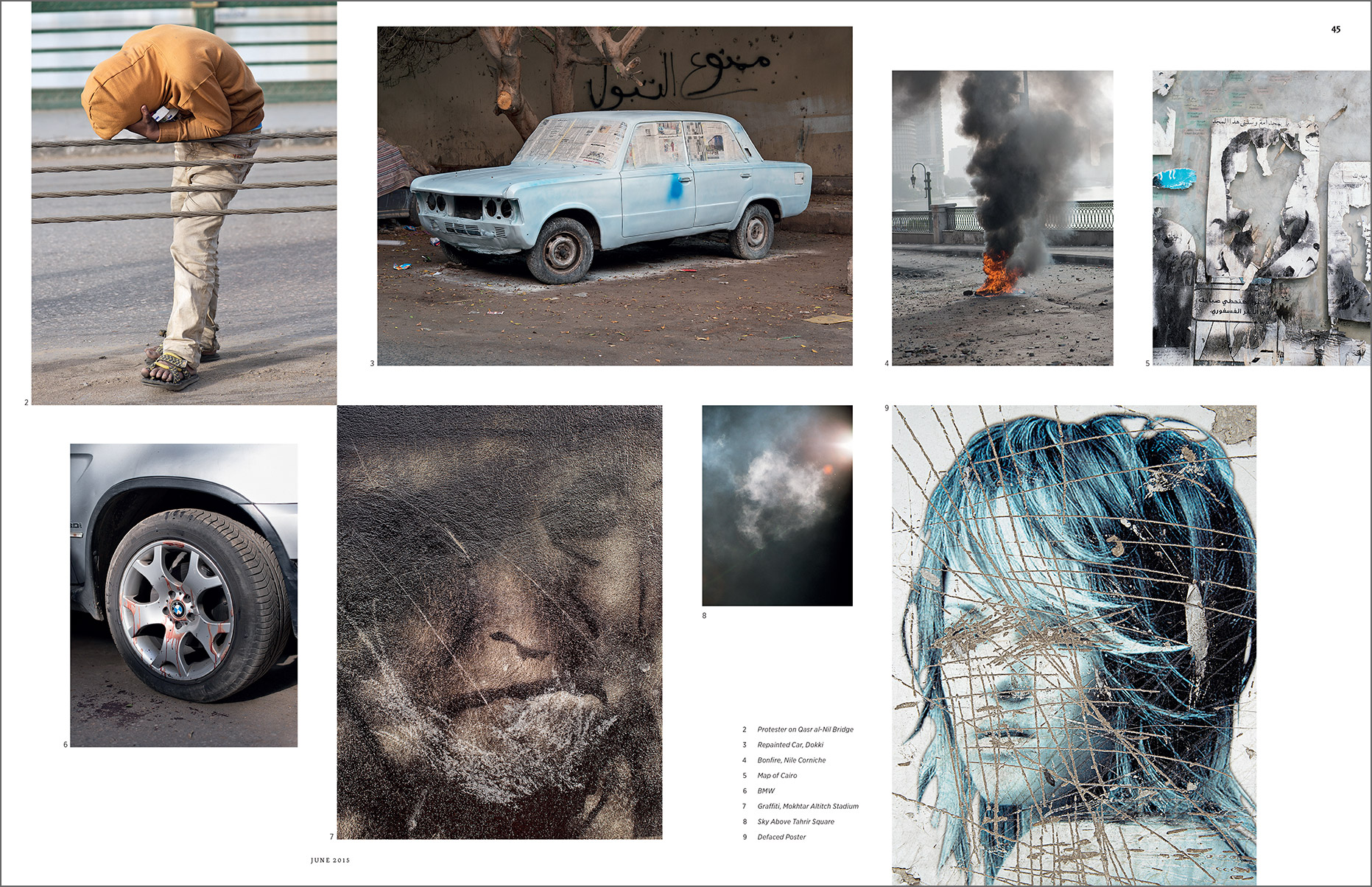

“It took a long time to build the sequence,” says Ceschel, “because of the sheer amount of work we had to sift through. But that process really defined the book. Matthew had shot quite a lot of explicitly violent photos, for example; scenes of things he had seen in the street. As we began the edit we realised the book was more powerful without these images. We were trying to build this sense of general threat, of impending violence, and hope, but never quite showing it. The traces were more interesting. Besides, those other kinds of images had already been covered.”

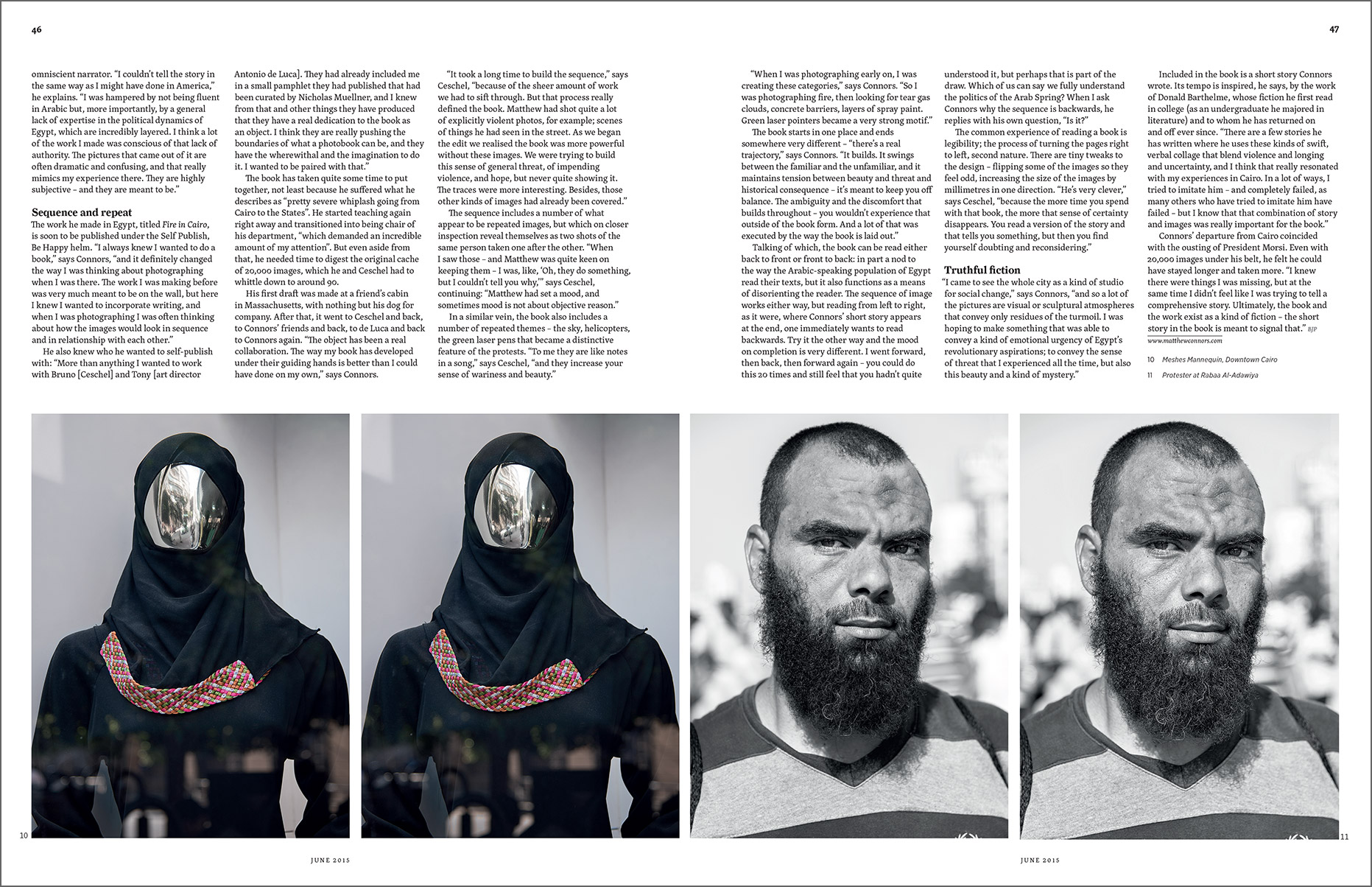

The sequence includes a number of what appear to be repeated images, but which on closer inspection reveal themselves as two shots of the same person taken one a!er the other. “When

I saw those – and Matthew was quite keen on keeping them – I was, like, ‘Oh, they do something, but I couldn’t tell you why,’” says Ceschel, continuing: “Matthew had set a mood, and sometimes mood is not about objective reason.”

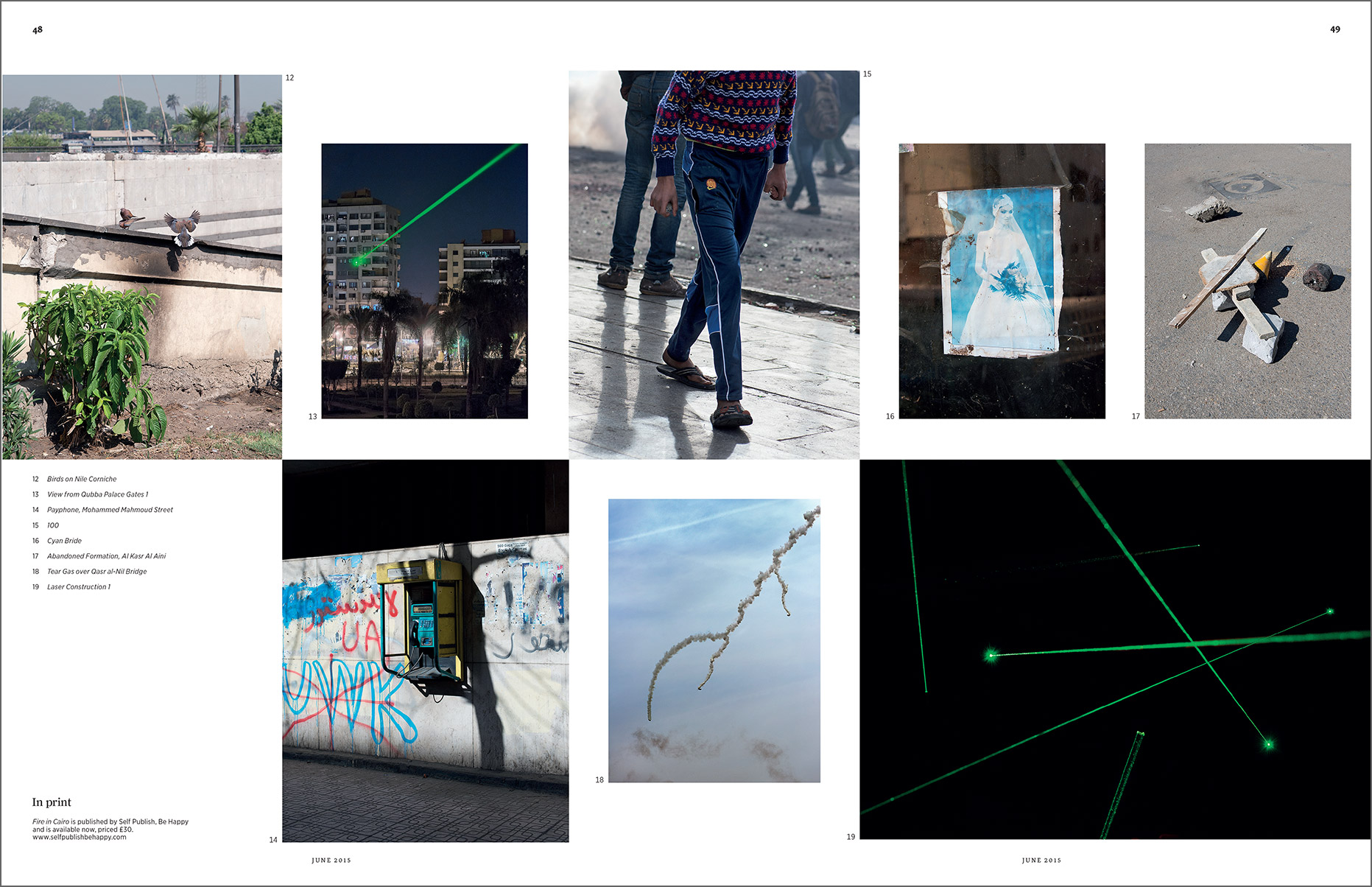

In a similar vein, the book also includes a number of repeated themes – the sky, helicopters, the green laser pens that became a distinctive feature of the protests. “To me they are like notes in a song,” says Ceschel, “and they increase your sense of wariness and beauty.”

“When I was photographing early on, I was creating these categories,” says Connors. “So I was photographing fire, then looking for tear gas clouds, concrete barriers, layers of spray paint. Green laser pointers became a very strong motif.”

The book starts in one place and ends somewhere very different – “there’s a real trajectory,” says Connors. “It builds. It swings between the familiar and the unfamiliar, and it maintains tension between beauty and threat and historical consequence – it’s meant to keep you off balance. The ambiguity and the discomfort that builds throughout – you wouldn’t experience that outside of the book form. And a lot of that was executed by the way the book is laid out.”

Talking of which, the book can be read either back to front or front to back: in part a nod to

the way the Arabic-speaking population of Egypt read their texts, but it also functions as a means of disorienting the reader. The sequence of image works either way, but reading from left to right, as it were, where Connors’ short story appears at the end, one immediately wants to read backwards. Try it the other way and the mood on completion is very different. I went forward, then back, then forward again – you could do this 20 times and still feel that you hadn’t quite understood it, but perhaps that is part of the draw. Which of us can say we fully understand the politics of the Arab Spring? When I ask Connors why the sequence is backwards, he replies with his own question, “Is it?”

The common experience of reading a book is legibility; the process of turning the pages right to left, second nature. There are tiny tweaks to the design – flipping some of the images so they feel odd, increasing the size of the images by millimetres in one direction. “He’s very clever,” says Ceschel, “because the more time you spend with that book, the more that sense of certainty disappears. You read a version of the story and that tells you something, but then you find yourself doubting and reconsidering.”

Truthful fiction

“I came to see the whole city as a kind of studio for social change,” says Connors, “and so a lot of the pictures are visual or sculptural atmospheres that convey only residues of the turmoil. I was hoping to make something that was able to convey a kind of emotional urgency of Egypt’s revolutionary aspirations; to convey the sense of threat that I experienced all the time, but also this beauty and a kind of mystery.”

Included in the book is a short story Connors wrote. Its tempo is inspired, he says, by the work of Donald Barthelme, whose fiction he first read in college (as an undergraduate he majored in literature) and to whom he has returned on and off ever since. “There are a few stories he has written where he uses these kinds of swift, verbal collage that blend violence and longing and uncertainty, and I think that really resonated with my experiences in Cairo. In a lot of ways, I tried to imitate him – and completely failed, as many others who have tried to imitate him have failed – but I know that that combination of story and images was really important for the book.”

Connors’ departure from Cairo coincided with the ousting of President Morsi. Even with 20,000 images under his belt, he felt he could have stayed longer and taken more. “I knew there were things I was missing, but at the same time I didn’t feel like I was trying to tell a comprehensive story. Ultimately, the book and the work exist as a kind of fiction – the short story in the book is meant to signal that.”

Lucy Davies

British Journal of Photography (June, 2015)

The images that came out of Matthew Connors’ time in Egypt are “dramatic and confusing”, he tells Lucy Davies, reflecting his own sense of disorientation. As the bigger picture unfolded, he knew he wanted to do a photobook, and working in collaboration with Self Publish, Be Happy, it evolved into a study of urgent social change

When in July 2013 Matthew Connors turned the key in the lock of his Brooklyn studio for the first time in a year, he had more than 27,000 image on the hard drive in his bag. A professor at the Massachusetts College of Art and Design in Boston since 2004 (he commutes once a week from New York City via train), he had spent the previous 12 months on sabbatical, travelling through Egypt and North Korea, photographing both.

He had arrived in Cairo in the run-up tthe second anniversary of the January 25th Revolution of 2011, when Egyptians had taketo the streets to end the three-decade-long presidency of Hosni Mubarak, one of a seriesof uprisings across the Middle East that became known as the Arab Spring. Connors admits to being shocked when he first saw Tahrir Square, the location in the centre of Cairo where the protesters had congregated. “I had come to know it mostly through journalistic images, wher it had been swarming with people and ful of encampments. But when I arrived in early January, none of that was there – the traffic was flowing. The only echo of this immense revolution was the graffiti on the walls.”

Prior to his sabbatical, he had spent almost a year photographing resistance activists participating in New York’s Occupy movement. Between 2011 and 2012 he visited sites of protest across the city, such as Zuccotti Park in lower Manhattan’s financial district, where a disparate, leaderless band of protesters had come together, each for their own cause, but under the now infamous slogan, ‘We are the 99%.’

“After the movement got up a little steam and a fair amount of media attention, there was a sense of it being this continuous tourist experience,” he told Big Red & Shiny magazine in 2013. “People would go down to Ground Zero, they would go shopping at Century 21, and then swing by Zuccotti Park to almost aggressively take pictures, not interacting with anyone. I saw how photography was being used to distance people from the movement and make them spectators.”

For his series General Assembly, Connors concocted a careful framework that was designed to initiate interactions with the protesters. He would take a portrait, talk to the subject about their involvement, obtain their contact information, email them the pictures, and then return with printed photographs to hand out. “It became an exchange of images and ideas,” he says. “Over time the pictures started to mean something different. After I had amassed several hundred, it became a portrait of the movement.”

Social landscape

Protest has always been something that 39-year-old Connors has had an affinity for, but until Occupy it had never found its way into his work. Having come to photography as a teen, “I was of that generation that was seduced by the alchemy and the magic of the darkroom.” Via an MFA in photography from Yale University, he had cut a furrow producing work that concerned, as he describes it, “urbanisation in a global context, the dynamics of interactions in the public sphere, the legacy of street photography, and the ontology of the medium during its recent technological evolution”.

The social landscape he discovered during the Occupy protests came to energise him like nothing else. Among the protestors he met in Zuccotti Park were a number of Egyptians who had come to New York following the success of their own demonstrations in Tahrir Square. “After conversations with them, I felt like I really needed to see events in Cairo first hand,” he says.

He made arrangements to stay with a former student from his college who was in Egypt on

a Fulbright Scholarship. They all lived in an apartment in Giza, within walking distance from Tahrir Square, across the Nile.

As the January 25th anniversary approached, protest activity began to ferment. “Cairo is a fascinating city in terms of its relationship to history,” says Connors. “You have all these streets and bridges named with dates, so the past always seems present in the geography. As significant dates in the young history of the revolution came close, I would see people coalescing nearby.”

Tahrir was often a site of activity, and because of its proximity to his apartment, Connors would make a point of passing through first thing in the morning to see what might be happening. But just as often, he’d witness activity at the Presidential Palace in Heliopolis, the Ultras stadium in Gezira, Qubba palace, the Qasr al-Nil bridge, other parts of downtown Cairo and later at the Muslim Brotherhood encampments at Rabaa Al-Adawiya mosque and Cairo University.

“It took me a while to understand the rhythms of the city,” says Connors. “Fridays were often really significant, usually accompanied by a strong outpouring of protest. I photographed whenever I could, but at some point in May it became almost unbearably hot, so I only went out to take pictures early in the morning. Things really slowed down as we got closer to Ramadan.”

Many of the pictures he took came in these “interstitial moments”, as he terms them, where he was simply walking around the city, either between sites of protest or early morning before anything was happening. Often it was a means of processing his experience, which he says was often marked by a feeling of unease. “My instincts weren’t always very good. I put myself in some pretty dangerous situations. I was shot with a tear gas canister once and it knocked me to the ground. At the time I thought it wasn’t that big a deal, but about a week before I left a young American college student was doing something relatively similar to what I was doing – standing on the periphery of a street conflict – and was stabbed in the chest. He died from that wound.”

He also felt uneasy about his position as omniscient narrator. “I couldn’t tell the story in the same way as I might have done in America,” he explains. “I was hampered by not being fluent in Arabic but, more importantly, by a general lack of expertise in the political dynamics of Egypt, which are incredibly layered. I think a lot of the work I made was conscious of that lack of authority. The pictures that came out of it are often dramatic and confusing, and that really mimics my experience there. they are highly subjective – and they are meant to be.”

Sequence and repeat

The work he made in Egypt, titled Fire in Cairo, is soon to be published under the Self Publish, Be Happy helm. “I always knew I wanted to do a book,” says Connors, “and it definitely changed the way I was thinking about photographing when I was there. The work I was making before was very much meant to be on the wall, but here I knew I wanted to incorporate writing, and when I was photographing I was o!en thinking about how the images would look in sequence and in relationship with each other.”

He also knew who he wanted to self-publish with: “More than anything I wanted to work with Bruno [Ceschel] and Tony [art director Antonio de Luca]. They had already included me in a small pamphlet they had published that had been curated by Nicholas Muellner, and I knew from that and other things they have produced that they have a real dedication to the book as an object. I think they are really pushing the boundaries of what a photobook can be, and they have the wherewithal and the imagination to do it. I wanted to be paired with that.”

The book has taken quite some time to put together, not least because he suffered what he describes as “pre"y severe whiplash going from Cairo to the States”. He started teaching again right away and transitioned into being chair of his department, “which demanded an incredible amount of my attention”. But even aside from that, he needed time to digest the original cache of 20,000 images, which he and Ceschel had to whi"le down to around 90.

His first draft was made at a friend’s cabin in Massachusetts, with nothing but his dog for company. After that, it went to Ceschel and back, to Connors’ friends and back, to de Luca and back to Connors again. The object has been a real collaboration. The way my book has developed under their guiding hands is better than I could have done on my own,” says Connors.

“It took a long time to build the sequence,” says Ceschel, “because of the sheer amount of work we had to sift through. But that process really defined the book. Matthew had shot quite a lot of explicitly violent photos, for example; scenes of things he had seen in the street. As we began the edit we realised the book was more powerful without these images. We were trying to build this sense of general threat, of impending violence, and hope, but never quite showing it. The traces were more interesting. Besides, those other kinds of images had already been covered.”

The sequence includes a number of what appear to be repeated images, but which on closer inspection reveal themselves as two shots of the same person taken one a!er the other. “When

I saw those – and Matthew was quite keen on keeping them – I was, like, ‘Oh, they do something, but I couldn’t tell you why,’” says Ceschel, continuing: “Matthew had set a mood, and sometimes mood is not about objective reason.”

In a similar vein, the book also includes a number of repeated themes – the sky, helicopters, the green laser pens that became a distinctive feature of the protests. “To me they are like notes in a song,” says Ceschel, “and they increase your sense of wariness and beauty.”

“When I was photographing early on, I was creating these categories,” says Connors. “So I was photographing fire, then looking for tear gas clouds, concrete barriers, layers of spray paint. Green laser pointers became a very strong motif.”

The book starts in one place and ends somewhere very different – “there’s a real trajectory,” says Connors. “It builds. It swings between the familiar and the unfamiliar, and it maintains tension between beauty and threat and historical consequence – it’s meant to keep you off balance. The ambiguity and the discomfort that builds throughout – you wouldn’t experience that outside of the book form. And a lot of that was executed by the way the book is laid out.”

Talking of which, the book can be read either back to front or front to back: in part a nod to

the way the Arabic-speaking population of Egypt read their texts, but it also functions as a means of disorienting the reader. The sequence of image works either way, but reading from left to right, as it were, where Connors’ short story appears at the end, one immediately wants to read backwards. Try it the other way and the mood on completion is very different. I went forward, then back, then forward again – you could do this 20 times and still feel that you hadn’t quite understood it, but perhaps that is part of the draw. Which of us can say we fully understand the politics of the Arab Spring? When I ask Connors why the sequence is backwards, he replies with his own question, “Is it?”

The common experience of reading a book is legibility; the process of turning the pages right to left, second nature. There are tiny tweaks to the design – flipping some of the images so they feel odd, increasing the size of the images by millimetres in one direction. “He’s very clever,” says Ceschel, “because the more time you spend with that book, the more that sense of certainty disappears. You read a version of the story and that tells you something, but then you find yourself doubting and reconsidering.”

Truthful fiction

“I came to see the whole city as a kind of studio for social change,” says Connors, “and so a lot of the pictures are visual or sculptural atmospheres that convey only residues of the turmoil. I was hoping to make something that was able to convey a kind of emotional urgency of Egypt’s revolutionary aspirations; to convey the sense of threat that I experienced all the time, but also this beauty and a kind of mystery.”

Included in the book is a short story Connors wrote. Its tempo is inspired, he says, by the work of Donald Barthelme, whose fiction he first read in college (as an undergraduate he majored in literature) and to whom he has returned on and off ever since. “There are a few stories he has written where he uses these kinds of swift, verbal collage that blend violence and longing and uncertainty, and I think that really resonated with my experiences in Cairo. In a lot of ways, I tried to imitate him – and completely failed, as many others who have tried to imitate him have failed – but I know that that combination of story and images was really important for the book.”

Connors’ departure from Cairo coincided with the ousting of President Morsi. Even with 20,000 images under his belt, he felt he could have stayed longer and taken more. “I knew there were things I was missing, but at the same time I didn’t feel like I was trying to tell a comprehensive story. Ultimately, the book and the work exist as a kind of fiction – the short story in the book is meant to signal that.”